Does anxiety run in families? Here's what genetics tells us

Last updated:

10/07/25, 18:26

Published:

19/06/25, 07:00

Research confirms anxiety disorders do have a genetic side

Have you ever noticed anxiety can pop up in several members of the same family? Maybe your sister worries constantly, or your brother gets nervous around people. It might feel like anxiety is passed down through generations. But is that really how it works, or is it just a coincidence?

Here's what science has to say.

Your DNA can affect anxiety

Research confirms anxiety disorders do have a genetic side. That means you're more likely to have anxiety if someone in your family, like your mum, dad, sibling, or even a grandparent, has it too. But this doesn't mean anxiety is certain. Instead, genes increase your chances, accounting for about 30% to 40% of your risk. Scientists work this out by comparing identical and fraternal twins and by following anxiety diagnoses across generations; those studies repeatedly find that roughly one-third to two-fifths of a person’s risk is genetic.

So, if genetics only make up part of the picture, what's the rest? That's where your environment steps in. Your life experiences matter a lot. Things like your relationships, stressful situations, and even your physical health can tip the scales one way or another. Genes set the stage, but they don't control the outcome.

Think of your genes as nudging you towards anxiety rather than pushing you into it completely. The rest depends on what happens to you.

How genes shape your brain

Scientists have pinpointed several genes linked to anxiety. One of these genes affects serotonin, a brain chemical that helps regulate your mood and manage stress. When serotonin works well, you feel calm and can handle stressful events better. But if your genes make serotonin less effective, stress hits you harder. This can make anxiety more likely during tough times, even when others around you seem okay.

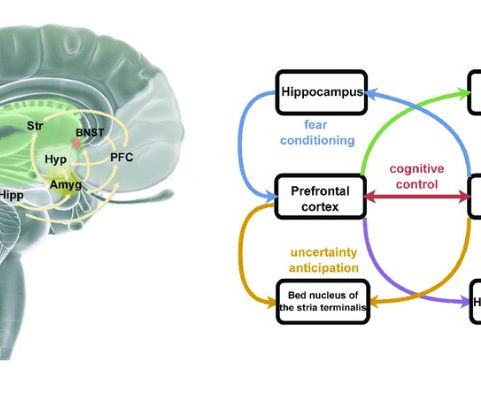

There's another important point: your brain structure. Genes influence parts of your brain, especially the amygdala. Think of the amygdala as your internal alarm system. It warns you when something feels dangerous. In people with certain genes, the amygdala is extra sensitive. That means their "alarm" goes off more easily, causing anxiety even when there's no real danger present.

However, not everyone with these genetic variations experiences anxiety. Your brain adapts throughout life, changing how genes affect you.

This ongoing flexibility is called neuroplasticity: experience can strengthen or weaken neural circuits and can even add or remove chemical tags, such as DNA methylation, that switch genes on or off, reshaping how your stress system responds.

Anxiety isn't just genetic; here's why

It's tempting to blame your genes entirely if anxiety runs in your family. But life is more complicated. Even if you inherit genes that make anxiety more likely, the disorder usually develops when certain environmental conditions come into play.

Stressful life events like losing a loved one, ongoing conflict at home, bullying, or trauma can trigger anxiety symptoms. Someone might have anxiety-related genes but never experience anxiety if their life stays relatively stress-free. On the other hand, someone without these genes can still develop anxiety if they experience severe stress or trauma.

Lifestyle choices also make a big difference. Regular exercise, healthy eating, good sleep, and support from friends and family can protect against anxiety. Studies show these lifestyle habits are powerful, even if your genes are pushing in the opposite direction.

Can you change your genetic destiny?

Understanding that anxiety has a genetic basis can help. It means anxiety isn't just a character flaw or personal weakness. It's something partly built into your biology, something real and valid. Realising this can reduce shame and make people more willing to seek help.

And here's another benefit: knowing your family history allows you to spot anxiety sooner. If you understand that anxiety might run in your family, you can pay attention to early signs, like trouble sleeping, excessive worry, or panic in social settings. Catching anxiety early means getting support earlier, making treatments like therapy or lifestyle changes more effective. Anxiety might run in your family, but you get to decide how far it goes.

Written by Rand Alanazi

Related articles: Depression / South Asian mental health / Physical and mental health / Does insomnia run in families?

REFERENCES

National Institute of Mental Health. Anxiety disorders [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Mental Health; 2024 [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders

Mayo Clinic. Anxiety disorders [Internet]. Rochester (MN): Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2018 [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

Leyfer O, Woodruff-Borden J, Mervis CB. Anxiety disorders in children with Williams syndrome, their mothers, and their siblings: implications for the aetiology of anxiety disorders. J Neurodev Disord. 2009 Feb 13;1(1):4-14.

Martin EI, Ressler KJ, Binder EB, Nemeroff CB. The neurobiology of anxiety disorders: brain imaging, genetics, and psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychiatr Clin North Am [Internet]. 2009 Sep;32(3):549-75. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3684250/

McEwen BS, Eiland L, Hunter RG, Miller MM. Stress and anxiety: structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation as a consequence of stress. Neuropharmacology. 2012 Jan;62(1):3-12.

Xie S, Zhang X, Cheng W, Yang Z. Adolescent anxiety disorders and the developing brain: comparing neuroimaging findings in adolescents and adults. Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 Aug 4;34(4):e100542. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8340272/

Zhang K, Ibrahim GM, Venetucci Gouveia F. Molecular pathways, neural circuits and emerging therapies for self-injurious behaviour. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2025 Feb 24;26(5):1938. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/5/1938

Chaves T, Fazekas CL, Horváth K, Correia P, Szabó A, Török B, et al. Stress adaptation and the brainstem with focus on corticotropin-releasing hormone. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1;22(16):9090. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/16/9090

Project Gallery