CEDS: a break in cell death

Last updated:

12/09/25, 11:08

Published:

11/09/25, 07:00

Looking at caspase-8’s inability to trigger cell death

This is article no. 11 in a series on rare diseases. Next article coming soon. Previous article: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Cell death, as we know it, is a crucial phenomenon by which our bodies remove unnecessary or damaged cells to maintain internal stability, a process known as homeostasis. Cell death can occur in many ways, but the mechanisms by which cells die follow two main paths. It may occur as naturally programmed, as in apoptosis, or as a result of toxic trauma or physical damage, like necrosis. While cell death due to trauma can often be more noticeable and dramatic, programmed cell death happens continually, not only because of cell damage but also because it is a normal part of development, and inducing it is a core function of immune system cells. In essence, cell death comes naturally, removing cells that are possibly damaged or infected to maintain the body as a whole.

But what if cell death stops? As many fiction stories will tell you, immortality is never a good thing, and this is accurate for our cells, too. Although excessive cell death is also destructive, cell death in its natural controlled manner not only stops the spread of infection but also prevents the survival of cancer cells and auto-reactive immune cells, which can damage the body by forming cancerous tumours and triggering autoimmune diseases, respectively. This demonstrates that a careful balance of life and death must always be in place to maintain homeostatic conditions and allow our unimpeded survival.

However, as cell death is a multi-step mechanism, it can go wrong in several ways. Furthermore, diseases causing faults in the cell death process can be challenging to diagnose. Not only can there be numerous reasons for patients to exhibit symptoms associated with the loss of cell death, but some of these reasons may also be rare disorders and, therefore, difficult for healthcare professionals to identify. One rare disease that researchers recently recognised is Caspase-8 Deficiency Syndrome (CEDS). This disease, stemming from a genetic mutation in the gene coding for caspase-8, results in extensive issues related to immunodeficiency, and they are all caused by caspase-8’s inability to trigger cell death.

So what is Caspase-8?

Caspase-8 is a pivotal regulator of the apoptotic pathway. Essentially, apoptosis can happen through two key pathways: the extrinsic pathway, when triggers originate outside the cell; and the intrinsic pathway, when the cell itself activates the cell death pathway. Whilst there are several key players in apoptosis, caspase-8 is a central mediator of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Caspase-8 can be activated through numerous ways, but it is often through so-called death receptors, which are typically members of the Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor (TNFR) family of transmembrane proteins. Upon their activation, a chain reaction occurs, involving the recruitment of caspase-8 into a complex, known as the death-inducing signalling complex (DISC). This complex then cleaves further downstream caspases or the BH3 Bcl2-interacting protein. This cascade leads to DNA fragmentation, degradation of the cytoskeleton, formation of apoptotic bodies, expression of ligands for phagocytic cell receptors, and finally, uptake by phagocytes, thus completing the death of the cell and its cleanup (Figure 2.).

Caspase-8 therefore plays a crucial role in completing the death inducing pathway. While there are other methods of cell death, the loss of Caspase-8 undoubtedly leads to significant consequences.

Caspase-8 deficiency syndrome (CEDS)

Scientists first discovered CEDs in the early 2000s. By this time, there had already been extensive research into a similar disease known as Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS), which results from defective apoptosis leading to abnormal immune cell survival. However, at the time of ALPS discovery, there was no identified link to a loss of Caspase-8. Furthermore, there was a lack of available mouse models to study, as inducing homozygous caspase-8 deficiency caused embryonic lethality in mice, significantly limiting research. Therefore, a loss of caspase-8 was also considered to have the same effect in humans.

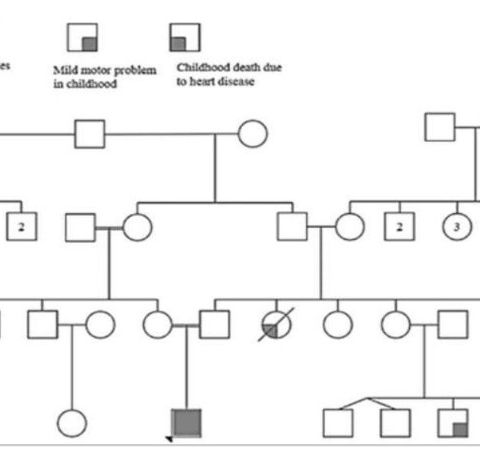

This train of thought continued until 2002, when Chun et al. conducted major studies into apoptosis-related diseases. During one of their many trials, two siblings—a 12-year-old girl and an 11-year-old boy—were found to exhibit symptoms similar to those of ALPS (lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and defective CD95-induced apoptosis of peripheral blood lymphocytes). However, unlike ALPS, the siblings were also immunodeficient and suffered from recurrent sinopulmonary and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections, as well as a poor response to immunisation.

Following the discovery of these additional symptoms in the siblings, researchers examined their other family members but were surprised to find that neither the parents nor another sibling suffered in a similar fashion. The only symptom they had was a partial defect in apoptosis mediated by CD95. It was determined that the mother, father, sibling, and several other extended family members were potentially heterozygous carriers of the mutation found in the affected siblings.

Subsequently, a DNA analysis was conducted, and a mutation was found in the CASP8 gene. This mutation was a homozygous deletion, which ultimately led to a loss of function of the caspase-8 protein. This loss of function in caspase-8 resulted in defective interleukin 2 production and diminished T-cell proliferation, explaining the immunodeficiency associated with CEDS and highlighting the important role caspase-8 plays in regulating cell death and immune responses.

Since CEDS was first identified in the 2002 study, very few cases have been reported in medical literature. However, despite this, research continues, and it has allowed further insights into caspase-8’s pathophysiology and, in many studies, new genetic variants have been identified. One such variant is a homozygous missense mutation resulting in significant immune dysregulation in an affected individual, which results in immune responses and inflammatory conditions associated with the disease.

Alongside research into the causes of this disease, focus has also shifted to how we might best diagnose and treat the disease and provide patients with the good quality of life they deserve.

Diagnosis

As with all rare diseases, one of the main issues stopping correct diagnosis of CEDS and delaying treatment is the fact healthcare providers are not familiar with disease symptoms, let alone the genetic basis of the disease. To make matters worse, the presentation of disease varies depending on the age of onset, which makes it even more difficult to recognise CEDS as the common underlying cause. For instance, early-onset often results in symptoms, such as severe infections and organomegaly, while adult-onset patients may present with neurological issues, multi-organ failure and chronic inflammatory conditions. Further adding to these diagnostic difficulties is the fact CEDS overlaps with other conditions, such as the previously mentioned ALPs. As a result, a patient could receive multiple different diagnoses before CEDS is identified as the cause of their suffering.

For effective CEDS diagnosis, expertise in immunology, genetics and infectious diseases is required. However, this specialised knowledge is hard to come by, and as with all diseases, the familiarity the healthcare provider has with it contributes greatly to whether you will get diagnoses, and this familiarity does not exist for rare diseases. Furthermore, diagnostic methods in general are tricky for this disease, with multiple tests often being required including an analysis of patient history alongside genetic testing through methods like whole exome sequencing and immunological tests analysing the types and states of immune cells and abnormal levels of immunoglobulins. Each of these diagnostic methods takes time, in an often-strained healthcare system, which can lead to a sense of helplessness in disease sufferers who only suffer more the longer they do not know what is wrong.

Treatments

Unfortunately for patients, a difficult diagnosis is not the only challenge they face, as there is currently no cure for CEDS, and no specific treatments. However, there are more general treatments available that could potentially alleviate symptoms and help individuals achieve some level of normality in their lives. The best possible way to approach treatment of CEDS, as with most immunodeficiency related diseases, would be to treat both the immune dysfunction and prevent recurrent infections. This could involve a multifaceted treatment plan tailored to the individual, aiming to avoid complications from immune dysfunction and improve quality of life.

Potential treatment plans could include the use of antibiotic and antiviral medications for recurrent infections, and also more complex treatments such as Immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IVIG). IVIG provides necessary antibodies to bolster patients’ immune system, when they are not able to themselves, which both helps avoid overuse of antibiotic and antiviral treatments and prevents infections in the first place before treatment is required. Alongside these treatment methods, due to it being a relatively unknown disease, CEDS patients will also require a great deal of supportive and hands on care. As part of this care patients could potentially be provided with a specialised diet plan with all the correct nutrition to help them combat any gastrointestinal issues (GI’s) associated with CEDS, as primary immunodeficiency patients have found this method to help with control of GIs.

In addition to current therapies several innovative approaches to treatment of genetic diseases are in development which could be used in CEDS treatment. Recent advances in gene therapy research offer new hope for treating immune deficiencies resulting from genetic defects, which means these therapies could potentially benefit CEDS patients. One promising method for gene therapy utilises CRISPR-Cas9 to correct the genetic mutations, such as those in CASP8 leading to CEDS. Another approach uses viral vectors to deliver functional genes into patients’ cells, and this could potentially deliver a functional CASP8 gene. Additionally, another very promising therapy, previously used for ALPS patients, involves genetically modifying stem cells to correct a faulty gene (such as the faulty CASP8 gene) before re-infusing them into the patient to produce healthy immune cells. These treatments could revolutionise the management of rare genetic diseases like CEDS.

The future for CEDS as a rare disease

Rare diseases like CEDS are often chronic and, in many cases, life threatening. Due to the scarcity of information on these conditions, few if any treatments exist. Furthermore, due to their rarity, patients of rare diseases are not only small in number but also dispersed worldwide, leading to a feeling of isolation as they rarely meet someone who shares in their experiences. However, as scientific research progresses, treatments and therapies become more effective and accessible, and with 72% of rare diseases, including CEDS, having a genetic basis, gene therapies appear incredibly promising. Yet, there is still a long way to go to fully realize their potential, and even more that can be done to help and support those who continue to suffer alone with rare diseases.

Written by Faye Boswell

REFERENCES

Telford WG. Multiparametric analysis of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1678:167–202. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8063493/

Smith C. Monitoring apoptosis by flow cytometry. Biocompare. 2017 Jan 17. Available from: https://www.biocompare.com/Editorial-Articles/332620-Monitoring-Apoptosiby-Flow-Cytometry/

Tummers B, Green DR. Caspase-8; regulating life and death. Immunol Rev. 2017 May;277(1):76–89. doi: 10.1111/imr.12541. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5417704/

Leeies M, Flynn E, Turgeon AF, Paunovic B, Loewen H, Rabbani R, Abou-Setta AM, Ferguson ND, Zarychanski R. High-flow oxygen via nasal cannulae in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 18;6(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0607-1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4439260/

Goyal A, Moitra D, Goldstein DB, Savage H, Lisco A, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Caspase-8 deficiency presenting as a novel immune dysregulation syndrome: case report and literature review. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2023;19(1):57. doi:10.1186/s13223-023-00778-3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10084589/

Chun HJ, Zheng L, Ahmad M, Wang J, Speirs CK, Siegel RM, et al. Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature. 2002 Sep 26;419(6905):395–9. doi:10.1038/nature01063. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12353035/

Khan S, Saha S, Saha S, et al. Early and frequent exposure to antibiotics in early childhood and risk of overweight: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22(3):e13113. doi:10.1111/obr.13113. Available from: https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)35036-4/fulltext

Casanova JL, Abel L. Caspase-8 deficiency syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:104. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00104. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7750663/

Castiello MC, Villa A. Stem cell editing repairs severe immunodeficiency. The Scientist. 2024 Mar 6. Available from: https://www.the-scientist.com/stem-cell-editing-repairs-severe-immunodeficiency-71733

Ha TC, Morgan M, Schambach A. Base editing: a novel cure for severe combined immunodeficiency. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):354. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01586-2. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-023-01586-2https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7750663/

Project Gallery