How human activity impacts the phosphorus cycle

Last updated:

27/12/25, 17:55

Published:

15/01/26, 08:00

Discussing eutrophication and industrial activities

Phosphorus is one of the most important chemical elements in biology because it is a component of nucleic acids, ATP, and the phospholipid bilayers that make up our cell membranes. Like carbon and nitrogen, there is a limited amount of phosphorus on Earth, which is continually cycled between inorganic, organic, terrestrial, and aquatic sources. However, human activity disrupts the phosphorus cycle, resulting in some places having too much phosphorus and others having too little. This article will describe what the phosphorus cycle is and how we are affecting it.

What is the phosphorus cycle?

The phosphorus cycle involves phosphate ions (PO43-) moving between rocks, living organisms, and water bodies. Phosphate enters ecosystems when wind and rain break off tiny pieces of phosphate rock, primarily apatite, in a process called weathering. Weathered phosphate rock enters soil, where micro-organisms transform it into a form that plants can absorb through their roots (see my previous article on this process, called phosphate solubilisation). Plants convert inorganic phosphate into organic phosphorus compounds, such as DNA, ATP, and phosphoproteins, which are then transferred along the food chain. At each step of the food chain, phosphorus is returned to the soil by excretion from living organisms or decomposition of dead organisms. I call this the ‘organic mini-cycle’ from soil, to plants, to animals, and back to soil. Occasionally, phosphorus leaves the organic mini-cycle and enters water bodies by leaching or soil erosion. Phosphorus settles on the seabed and turns back into phosphate rock over hundreds of millions of years, completing the cycle. An overview is shown in Figure 1.

Humans disrupt the phosphorus cycle by eutrophication

Deforestation, farming, and sewage overload water bodies with nutrients like phosphorus in a process called eutrophication. Agriculture is a big source of eutrophication, specifically fertilisers, organophosphorus pesticides, and animal feed. When it rains, they are carried from farm soil to water bodies by surface runoff and soil erosion. Human-caused deforestation exaggerates eutrophication because without tree roots, soil erosion increases, so more agricultural phosphorus enters water bodies. The other big eutrophication source is domestic sewage, which is dumped directly into water bodies.

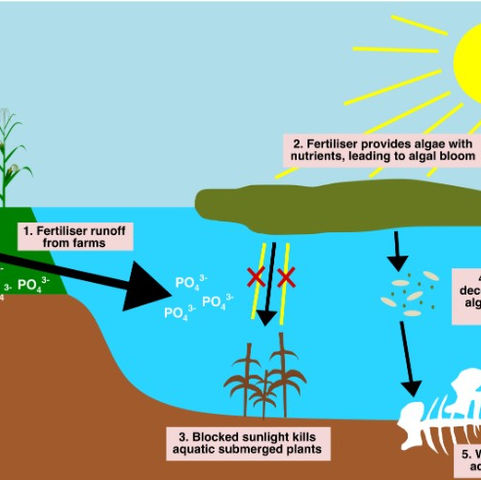

Fertilisers, pesticides, animal feed, and sewage provide algae with excess nutrients, so they overgrow into an algal bloom (Figure 2). Algal blooms block sunlight from reaching submerged aquatic plants, so they cannot photosynthesise, and may produce toxins that kill aquatic life. Once the algal bloom dies, it is decomposed by bacteria, which use up oxygen in the water. With oxygen used up and no photosynthesis to replace it, fish and other aquatic animals die. Therefore, human phosphorus inputs like fertilisers and domestic waste can destroy aquatic ecosystems.

Industrial activity depletes non-renewable phosphate rock

While human activities overload water bodies with phosphorus, they deplete land of phosphate rock. Phosphate rock is mined and chemically reacted with sulfuric acid to produce fertiliser. Since phosphate rock is non-renewable, mining it permanently removes a crucial phosphorus input from the local ecosystem. 85% of phosphate rock is found in only 5 countries (China, Morocco, South Africa, Algeria, and Syria), so these countries are being depleted of phosphorus, only to overload another ecosystem with fertiliser thousands of miles away (Figure 3).

Scientists have suggested using agricultural waste and domestic wastewater as an alternative phosphorus source for fertiliser production. This would rebalance the phosphorus cycle on both ends: reducing the demand for non-renewable phosphate rock, and preventing eutrophication. Phosphorus can be recovered from waste and reused in fertiliser production in a variety of ways – acid leaching, isolating iron phosphate using a magnet, metal precipitation, and polyphosphate-accumulating micro-organisms, which use and store phosphate in their cells. However, the pollution and diseases present in sewage and farm waste make them difficult to recycle.

Conclusion

Phosphorus is an essential element for plant growth, so humans have manufactured fertilisers to provide their crops with extra phosphorus. However, fertiliser production depletes some ecosystems of phosphate rock, while fertiliser application causes eutrophication in other ecosystems. Along with domestic sewage and deforestation, agriculture has disrupted the natural cycle, which transports phosphate between plants, animals, micro-organisms, the soil, water bodies, and rocks. Therefore, making fertiliser by recycling the phosphorus in our waste products could keep the human population fed without compromising natural ecosystems.

Written by Simran Patel

Related article: Meet the microbes that feed phosphorus to plants

REFERENCES

Schipanski ME, Bennett EM. Chapter 9 - The Phosphorus Cycle. In: Weathers KC, Strayer DL, Likens GE (eds) Fundamentals of Ecosystem Science (Second Edition). Academic Press, pp. 189–213.

R. Jupp A, Beijer S, C. Narain G, et al. Phosphorus Recovery and Recycling – Closing the Loop. Chemical Society Reviews 2021; 50: 87–101.

Khan MN, Mohammad F. Eutrophication: Challenges and Solutions. In: Ansari AA, Gill SS (eds) Eutrophication: Causes, Consequences and Control: Volume 2. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1–15.

Akinnawo SO. Eutrophication: Causes, consequences, physical, chemical and biological techniques for mitigation strategies. Environmental Challenges 2023; 12: 100733.

Liu L, Zheng X, Wei X, et al. Excessive Application of Chemical Fertilizer and Organophosphorus Pesticides Induced Total Phosphorus Loss from Planting Causing Surface Water Eutrophication. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 23015.

Project Gallery