Regulation and policy of stem cell research

Last updated:

20/10/25, 14:40

Published:

23/10/25, 07:00

The 14-day rule and stem cell-based embryo models

This is the last article (article no. 3) in a three-part series on stem cells. Previous article: The role of mesenchymal stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Welcome to the final article in this series of three articles about stem cells. Article 1 was an overview of stem cells, and Article 2 focused on mesenchymal stem cells. In Article 3, I will look at the regulation and policy of stem cell research, which is important given the rapidly changing landscape of stem cell research.

Introduction

If used effectively, stem cells can be used in treating diseases, understanding human development, and more. For example, a recent paper published in September 2025 explains how scientists created embryos from human skin DNA, in an experimental process they named “mitomeiosis”. Here, the scientists attempted to force the egg cell to divide to remove half of its chromosomes so it could be fertilised like a normal egg cell. While mitomeiosis was unsuccessful in creating viable egg cells, new advancements like this raise ethical questions about the use of stem cells, especially those derived from embryos.

As a result, policies and regulations must be created and followed to ensure stem cells are used ethically and appropriately. Two major topics in this policy landscape are the 14-day rule for using human embryos and the creation of Stem Cell-Based Embryo Model (SCBEM) frameworks.

The 14-day rule

One of the most widely known restrictions in the field of stem cells is the 14-day rule. The 14-day rule prohibits scientists from culturing human embryos in vitro (in the laboratory) beyond 14 days or the appearance of the primitive streak. The primitive streak is a developmental marker signalling the point at which an embryo is biologically individualised. The appearance of this streak also marks the beginning of gastrulation, which is when embryonic cells start differentiating into the three primary germ layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. A timeline of human embryo development from day 0 to day 14 is shown in Figure 1 to help visualise the different stages.

In the UK, the 14-day rule is a law under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology (HFE) Act 1990 (as amended 2008). These human embryos are either donated with consent for research purposes due to no longer being needed, are unsuitable for fertility treatments, or are embryos created explicitly from donated sperm and eggs for research purposes.

However, scientific advances have meant that human embryo cultures have now become advanced, resulting in embryos being destroyed at the 14-day deadline due to the law. For example, in 2016, researchers developed new in vitro culture systems that allowed human embryos to be maintained in the lab up to the 12th and 13th day of development. This had previously not been possible. Unfortunately, the experiments had to be stopped because they were approaching the 14-day legal limit.

Therefore, scientists have questioned whether the 14-day rule is still fit-for-purpose, and if not, how it could be amended in a way that still ensures ethical and appropriate use of these cells. A specific area of development that scientists do not have a lot of information on is the “black box” period, which includes the moment of gastrulation, happening around day 14-15. Having further knowledge of gastrulation could be used to improve the success rate of In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF), by helping scientists to understand possible causes of early miscarriage and implantation failure, and working to mitigate those.

Because of this debate, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics has launched a project to better understand the arguments for and against extensions to the 14-day limit on human embryo research. The Council aims to use this project to provide decision-makers, such as policymakers, with the evidence they need to decide whether to extend the time limit.

Regulating Stem Cell-Based Embryo Models (SCBEMs)

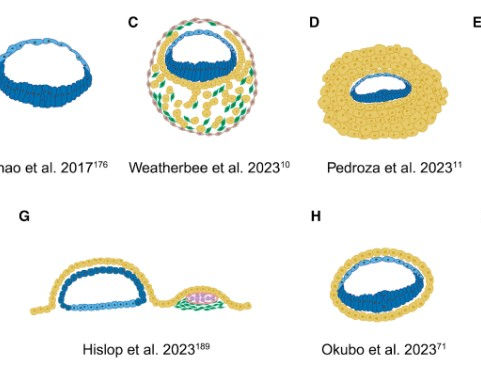

There is also the development of SCBEMs to consider, as seen in Figure 2. SCBEMs are also called embryoids or embryo models. They are complex, organised three-dimensional structures derived from pluripotent stem cells, which are cells that can differentiate into all cells in the human body.

SCBEMs replicate certain features and processes of embryonic development, meaning they can provide new insights into stages of early human development that have been normally inaccessible to scientists. However, SCBEMs are not defined as embryos under existing laws, like the HFE Act 1990, meaning there is a policy and regulation gap covering these structures.

To fill this gap, researchers recently created the first-ever UK guidelines for generating and using SCBEMs in research. The new SCBEM Code of Practice was published in July 2024 and has clear guidance and standards, increasing the transparency of research that will be conducted using SCBEMs. The Code requires that research have well-justified scientific objectives and adhere to an approved culture period, the minimum duration needed to achieve the scientific objective. For example, the Code prohibits the transfer of human SCBEMs into a human or animal womb.

Furthermore, adherence to the Code requires that a dedicated SCBEM Oversight Committee be created to review and approve proposed work. An SCBEM Register is also needed to record information about successful applications. Both of these increase the transparency and openness of research using SCBEMs.

Future of regulation and policy of stem cell research

Given the rapid pace of development in stem cell research, policies and regulations must be created and followed to ensure ethical and appropriate use of these cells. The review by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics regarding the 14-day rule will be important in determining if the rule should be extended. The extension could allow scientists to study developmental stages such as gastrulation, currently part of the “black box” period of development occurring after 14 days.

The creation of the UK's first-ever SCBEM Code of Practice in July 2024 has introduced guidelines to fill the existing policy gap, requiring research using these models to have well-justified scientific objectives, follow approved culture periods, and be reviewed by an Oversight Committee to ensure transparency and ethical use. However, there is a need for stronger regulations, as opposed to guidelines, for using SCBEMs, and it is an important example of where policy needs to continue to be developed.

Written by Naoshin Haque

Related articles: Animal testing ethics / How colonialism, geopolitics and health are interwoven

Project Gallery